To understand the impact of Jackson Pollack one has to consider the time in which the Paintings where conceived and created and the radical concept that was implicit in these works, its easy now to assimilate and to process this and there is no difficulty in understanding an art that goes beyond the borders of what was defined.But if one reflects on that point in time then its possible to really understand what these actions truly represented was a total break from the constrains that existed and an opening of the doors of new possibilities of aesthetics. A.Newton

This Article is edited and compiled from the Essay by Alan Kaprow first published in 1958

When the Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock died in 1956, the New York art world knew, almost immediately, that it had lost one of the 20th century’s most important artists. But what, exactly, was the impact of his work at the time? This was the artist Allan Kaprow’s question when he wrote the essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” originally published in the October 1958 issue of ARTnews. In his essay, Kaprow writes about what he calls “the Act of Painting”—the way in which Pollock turned painting into a ritualistic performance of sorts, rethinking the art- making process as an activity that took place in time and made use of the body. This was something that Kaprow himself would come to rely on in his so-called “happenings,” in which paintings became props in larger, temporary events that cast viewers as participants. Yet Kaprow’s essay also takes Pollock to task for the cult of personality he had developed.

The Legacy of Jackson Pollock , By Allan Kaprow October 1958

The problem of Jackson Pollock, two years after his death is of paramount importance. The examples of his life and revolutionary style are increasingly, and not always benignly, influential, for his career has encouraged some artists in the perilous belief that self-destruction is necessary to the integrity of a work of art. Here a young vanguard painter attempts to separate the man from the myth, and also to suggest what Pollock will mean to artists in 1960.

The tragic news of Pollock’s death two summers ago was profoundly depressing to many of us. We felt not only a sadness over the death of a great figure, but in some deeper way that something of ourselves had died too. We were a piece of him; he was, perhaps, the embodiment of our ambition for absolutely liberation and a secretly cherished wish to overturn old tables of crockery and flat champagne. We saw in his example the possibility of an astounding freshness, a sort of ecstatic blindness.

But, in addition, there was a morbid side to his meaningfulness. To “die at the top” for being his kind of modern artist was, to many, I think, implicit in the work before he died. It was this bizarre consequence that was so moving. We remembered van Gogh and Rimbaud. But here it was in our time, in a man some of us knew. This ultimate, sacrificial aspect of being an artist, while not a new idea, seemed, the way Pollock did it, terribly modern, and in him the statement and the ritual were so grand, so authoritative and all-encompassing in its scale and daring, that whatever our private convictions, we could not fail to be affected by its spirit.

It was probably this latter side of Pollock that lay at the root of our depression. Pollock’s tragedy was more subtle than his death; for he did not die at the top. One could not avoid the fact that during the last five years of his life his strength had weakened and during the last three, he hardly worked at all. Though everyone knew, in the light of reason, that the man was very ill (and his death was perhaps a respite from almost certain future suffering), and that, in point of fact, he did not die as Stravinsky’s fertility maidens did, in the very moment of creation/annihilation — we still could not escape the disturbing itch (metaphysical in nature) that this death was in some direct way connected with art. And the connection, rather than being climactic, was, in a way, inglorious. If the end had to come, it came at the wrong time.

Was it not perfectly clear that modern art in general was slipping? Either it had become dull and repetitious qua the “advanced” style, or large numbers of formerly committed contemporary painters were defecting to earlier forms. America was celebrating a “sanity in art” movement and the flags were out. Thus, we reasoned, Pollock was the center in a great failure: the New Art. His heroic stand had been futile. Rather than releasing a freedom, which it at first promised, it caused him not only a loss of power and possible disillusionment, but a widespread admission that the jig was up. And those of us still resistant to this truth would end the same way, hardly at the top. Such were our thoughts in August, 1956.

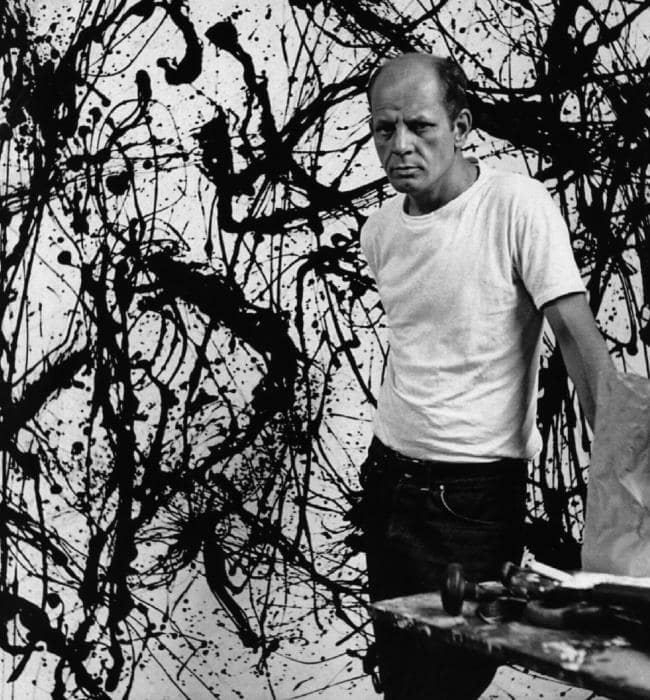

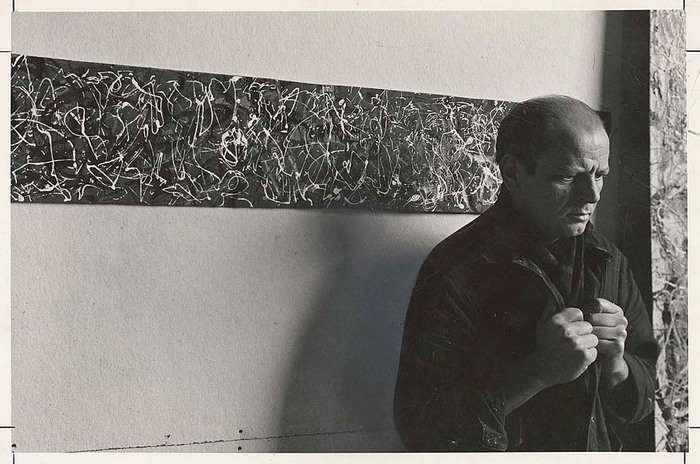

Photograph / Arnold Newman

but over two years have passed. What we felt then was genuine enough, but it was a limited tribute, if it was that at all. It was surely a manifestly human reaction on the part of those of us who were devoted to the most advanced of artists around us and who felt the shock of being thrown out on our own. But it did not actually seem that Pollock had indeed accomplished something, both by his attitude and by his very real gifts, which went beyond even those values recognized and acknowledged by sensitive artists and critics. The “Act of Painting,” the new space, the personal mark that builds its own form and meaning, the endless tangle, the great scale, the new materials, etc. are by now clichés of college art departments. The innovations are accepted. They are becoming part of text books.

But some of the implications inherent in these new values are not at all as futile as we all began to believe; this kind of painting need not be called the “tragic” style. Not all the roads of this modern art lead to ideas of finality. I hazard the guess that Pollock may have vaguely sensed this, but was unable, because of illness or otherwise, to do anything about it.

He created some magnificent paintings. But he also destroyed painting. If we examine a few of the innovations mentioned above, it may be possible to see why this is so.

For instance, the “Act of Painting.” In the last seventy-five years the random play of the hand upon the canvas or paper has become increasingly important. Strokes, smears, lines, dots, etc. became less and less attached to represented objects and existed more and more on their own, self-sufficiently. But from Impressionism up to, say, Gorky, the idea of an “order” to these markings was explicit enough. Even Dada, which purported to be free of such considerations as “composition,” obeyed the Cubist esthetic. One colored shape balanced (or modified, or simulated) others and these in turn were played off against (or with) the whole canvas, taking into account its size and shape—for the most part, quite consciously. In short, part-to-whole or part-to-part relationships, no matter how strained, were at least a good fifty percent of making the picture. (Most of the time it was a lot more, maybe ninety percent). With Pollock, however, the so-called “dance” of dripping, slashing, squeezing, daubing and whatever else went into a work, placed an almost absolute value upon a diaristic gesture. He was encouraged in this by the Surrealist painters and poets, but next to him their work is consistently “artful,” “arranged” and full of finesse—aspects of outer control and training. With a choice of enormous scales, the canvas being placed upon the floor, thus making difficult for the artist for the artist to see the whole or any extended section of “parts,” Pollock could truthfully say he was “in” his work. Here the direct application of an automatic approach to the act makes it clear that not only is this not the old craft of painting, but it is perhaps bordering on ritual itself, which happens to use paint as one of its materials. (The European Surrealists may have used automatism as an ingredient but hardly can we say they really practiced it wholeheartedly. In fact, it is only in a few instances that the writers, rather than the painters, enjoyed any success in this way. In retrospect, most of the Surrealist painters appear to be derived from a psychology book or from each other: the empty vistas, the basic naturalism, the sexual fantasies, the bleak surfaces so characteristic of this period have always impressed most American artists as a collection of unconvincing clichés. Hardly automatic, at that. And such real talents as Picasso, Klee and Miro belong more to the stricter discipline of Cubism than did the others, and perhaps this is why their work appears to us, paradoxically, more free. Surrealism attracted Pollock, as an attitude rather than as a collection of artistic examples.

There where Seven in Eight / 1945 MOMA NYC

But I used the words “almost absolute” when I spoke of the diaristic gesture as distinct from the process of judging each move upon the canvas. Pollock, interrupting his work, would judge his “acts” very shrewdly and with care for long periods of time before going into another “act.” He knew the difference between a good gesture and a bad one. This was his conscious artistry at work and it makes him a part of the traditional community of painters. Yet the distance between the relatively self-contained works of the Europeans and the seemingly chaotic, sprawling works of the American indicate at best a tenuous connection to “paintings.” (In fact, Jackson Pollock never really had a “malerisch” sensibility. The painterly aspects of his contemporaries, such as Motherwell, Hofmann, de Kooning, Rothko, even Still, point up, if at one moment a deficiency in him, at another moment, a liberating feature—and this one I choose to consider the important one.)

I am convinced that to grasp a Pollock’s impact properly, one must be something of an acrobat, constantly vacillating between an identification with the hands and body that flung the paint and stood “in” the canvas, and allowing the markings to entangle and assault one into submitting to their permanent and objective character. This is indeed far from the idea of a “complete” painting. The artist, the spectator and the other world are much too interchangeably involved here. (And if one objects to the difficulty of complete comprehension, I insist that he either asks too little of art or refuses to look at reality.)

Convergence 1952 / Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo : Oil on Canvas

Then Form. In order to follow it, it is necessary to get rid of the usual idea of “Form,” i.e. a beginning, middle and end, or any variant of this principle—such as fragmentation. You do not enter a painting of Pollock’s in any one place (or hundred places). Anywhere is everywhere and you can dip in and out when and where you can. This has led to remarks that his art gives one the impression of going on forever—a true insight. It indicates that the confines of the rectangular field were ignored in lieu of an experience of a continuum going in all directions simultaneously, beyond the literal dimensions of any work. (Though there is evidence pointing to a probably unknowing slackening of the attack as Pollock came to the edges of his canvas, he compensated for this by tacking much of the painted surface around the back of his stretchers.) The four sides of the painting are thus an abrupt leaving-off of the activity which our imaginations continue outward indefinitely, as though refusing to accept the artificiality of “ending.” In an older work, the edge was a far more precise caesura: here ended the world of the artist; beyond began the world of the spectator and “reality.”

We accept this innovation as valid because the artist understood with perfect naturalness “how to do it.” Employing an iterative principle of a few highly charged elements constantly undergoing variation (improvising, like much Oriental music) Pollock gives us an all-over unity and at the same time a means continuously to respond to a freshness of personal choice. But this type of form allows us just as well an equally strong pleasure in participating in a delirium, a deadening of the reasoning faculties, a loss of “self” in the Western sense of the term. It is this strange combination of extreme individuality and selflessness which makes the work not only remarkably potent, but also indicative of a probably larger frame of psychological reference. And it is for this reason that any allusions to Pollock’s being the marker of giant textures are completely incorrect. The point is missed and misunderstanding is bound to follow.

But given the proper approach, a medium-sized exhibition space with walls totally covered by Pollocks, offers the most complete and meaningful sense of his art possible.

Summertime: Number 9A 1948

© Pollock – Krasner Foundation, Inc.

Then scale. Pollock’s choice of enormous sizes served many purposes, chief of which for our discussion is the fact that by making mural-scale paintings, they ceased to become paintings and became environments. Before a painting, one’s size as a spectator, in relation to that of the picture, profoundly influences how much we are willing to give up the consciousness of our temporal existence while experiencing it. Pollock’s choice of great sizes resulted in our being confronted, assaulted, sucked in. Yet we must not confuse these with the hundreds of large paintings done in the Renaissance. They glorified an everyday world quite familiar to the observer, often, in fact, by means of trompe l’oeil, continuing the actual room into the painting. Pollock offers us no such familiarity and our everyday world of convention and habit is replaced by that one created by the artist. Reversing the above procedure, the painting is continued on out into the room.

Photograph / Arnold Newman

And this leads to our final point: Space. The space of these creations is not clearly palpable as such. One can become entangled in the web to some extent, and by moving in and out of the skein of lines and splashings, can experience a kind of spatial extension. But even so, this space is an allusion far more vague than even the few inches of space-reading a Cubist work affords. It may be that we are too aware of our need to identify with the process, the making of the whole affair, and this prevents a concentration on the specifics of before and behind, so important in a more traditional art. But what I believe is clearly discernible is that the entire painting comes out at the participant (I shall call him that, rather than observer) right into the room. It is possible to see in this connection how Pollock is the terminal result of a gradual trend that moved from the deep space of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, to the building out from the canvas of the Cubist collages. In the present case the “picture” has moved so far out that the canvas is no longer a reference point. Hence, although up on the wall, these marks surround us as they did the painter at work, so strict a correspondence has there been achieved between his impulse and the resultant art.

What we have then, is a type of art which tends to lose itself out of bounds, tends to fill our world with itself, an art which, in meaning, looks, impulse, seems to break fairly sharply with the traditions of painters back to at least the Greeks. Pollock’s near destruction of this tradition may well be a return to the point where art was more actively involved in ritual, magic and life than we have known it in our recent past. If so, it is an exceedingly important step, and in its superior way, offers a solution to the complaints of those who would have us put a bit of life into art. But what do we do now?

Photograph / Hans Namuth

There are two alternatives. One is to continue in this vein. Probably many good “near-paintings” can be done varying this esthetic of Pollock’s without departing from it or going further. The other is to give up the making of paintings entirely, I mean the single, flat rectangle or oval as we know it. It has been seen how Pollock came pretty close to doing so himself. In the process, he came upon some newer values which are exceedingly difficult to discuss, yet they bear upon our present alternative. To say that he discovered things like marks, gestures, paint, colors, hardness, softness, flowing, stopping, space, the world, life, death—is to sound either naïve or stupid. Every artist worth his salt has “discovered” these things. But Pollock’s discovery seems to have a peculiarly fascinating simplicity and directness about it. He was, for me, amazingly childlike, capable of becoming involved in the stuff of his art as a group of concrete facts seen for the first time. There is, as I said earlier, a certain blindness, a mute belief in everything he does, even up to the end. I urge that this be not seen as a simple issue. Few individuals can be lucky enough to possess the intensity of this kind of knowing, and I hope that in the near future a careful study of this (perhaps) Zen quality of Pollock’s personality will be undertaken. At any rate, for now, we may consider that, except for rare instances, Western art tends to need many more indirections in achieving itself, placing more or less equal emphasis upon “things” and the relations between them. The crudeness of Jackson Pollock is not, therefore, uncouth or designed as such; it is manifestly frank and uncultivated, unsullied by training, trade secrets, finesse—a directness which the European artists he liked hoped for and partially succeeded in, but which he never had to strive after because he had it by nature. This by itself would be enough to teach us something.

Lavender Mist: Number 1 (1950)

Pollacks Studio / Springs Long Island / Arnold Newman

It does. Pollock, as I see him, left us at the point where we must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life, either our bodies, clothes, rooms, or, if need be, the vastness of Forty-Second Street. Not satisfied with the suggestion through paint of our other senses, we shall utilize the specific substances of sigh, sound, movements, people, odors, touch. Objects of every sort are materials for the new art: paint, chairs, food, electric and neon lights, smoke, water, old socks, a dog, movies, a thousand other things which will be discovered by the present generation of artists. Not only will these bold creators show us, as if for the first time, the world we have always had about us, but ignored, but they will disclose entirely unheard of happenings and events, found in garbage cans, police files, hotel lobbies, seen in store windows and on the streets, and sensed in dreams and horrible accidents. An odor of crushed strawberries, a letter from a friend or a billboard selling Draino; three taps on the front door, a scratch, a sigh or a voice lecturing endlessly, a blinding staccato flash, a bowler hat—all will become materials for this new concrete art.

The Deep 1953

The young artist of today need no longer say “I am a painter” or “a poet” or “a dancer.” He is simply an “artist.” All of life will be open to him He will discover out of the ordinary things the meaning of ordinariness. He will not try to make them extraordinary. Only their real meaning will be stated. But out of nothing he will devise the extraordinary and then maybe nothingness as well. People will be delighted or horrified, critics will be confused or amused, but these, I am sure, will be the alchemies of the 1960s.